Palm Sunday

Sunday morning: for Jews, the day after

the Sabbath. After a day of quiet rest in their homes, people thronged the

streets of Jerusalem, joining the usual rush, but with an added edge. From the

west, Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor, was riding into Jerusalem at the head

of a column of imperial cavalry; the people quaked in fear. He'd come to

intimidate, and to keep that sort of peace that is nothing but trembling fear.

But then rumors spread: another great

man is riding in from the east, not on a war stallion or in a chariot, but on a

humble donkey. Jesus, descending the Mt. of Olives into the Kidron Valley, then

through the gates of the Holy City. Excitement mixed with confusion: Jesus had

won quite a reputation - so would he be the one to lead the rabble in rebellion

against the Romans?

Jesus, as was often the case,

disappointed, even before the cries of "Hosanna!" settled down. No

sword was hidden under his tunic, and if anybody flashed a weapon he sternly

but lovingly said "Put your sword away." He seemed more likely to be

killed than to kill. He came into Jerusalem, not avoiding those who feared him

or misunderstood him. He engaged, he demanded a decision - and across the

centuries, he still confronts all of us with God's humble compassion, ready to

bear all injustice in order to redeem it, prepared to be ridiculed to rescue

our ridiculous lives, relentless in his mission of saving grace.

So now we can grasp the pathos of that

children's hymn: "Tell me the stories of Jesus... Into the city I'd

follow... waving a branch of the palm tree high in my hand." We follow,

yes - and much courage will be required. Jesus knew he was in for a rough week

- and across the years he invites us to follow, trembling a bit and yet

confident in him, bracing for what may come, trusting that the dawning of the

next Sunday, the Easter resurrection Sunday, cannot be thwarted.

Prayer: Lord Jesus, thank you for

entering Jerusalem and our lives, thank you for your courage, your

determination, your mission, for showing us the divine heart. Help me to follow

- but I'll need you to give me some courage, and strength, and mostly love to

be close to you, to do whatever you ask, to be a humble, fearless servant in

Your kingdom."

Holy Monday

Monday morning.

Jesus walked two miles from Bethany into Jerusalem, a daunting, steep, rocky

road. Even rockier was the reception he got from the religious leaders: he

waltzed right into the temple, and in a rage that startled onlookers, drove the

moneychangers out of the temple.

Was he issuing a

dramatic memo against Church fundraisers? Hardly. He was acting out,

symbolically, God's judgment on the temple. The well-heeled priests, Annas and

Caiaphas, had sold out to the Romans. Herod had expanded the temple into one of

the wonders of the world - but he pledged his allegiance to Rome by placing a

large golden eagle, symbol of Roman power, over its gate. The people were no

better: a superficial religiosity masqueraded as the real thing. Within a

generation of Jesus’ Holy Monday, that seemingly indestructible temple was

nothing but rubble.

Jesus was not the

first to denounce the showy façade of a faked religiosity among God's people.

Through the centuries, Jeremiah, Isaiah, Micah, and John the Baptist had spoken

God's words of warning to people whose spiritual lives were nothing more than

going through the motions, assuming God would bless and protect them even

though their lives did not exhibit the deep commitment God desired. God's

prophets who spoke this way were not honored, but mocked, arrested, imprisoned,

and even executed. Jesus was courting disaster.

On that Monday of

the first Holy Week, Jesus shut down operations in the temple and forecast its

destruction. No wonder the authorities wanted to kill Jesus! In a way, Jesus

would himself become a kind of substitute temple. The temple was the place, the

focal point of humanity's access to God. Jesus, like the temple itself, was

destroyed, killed - and his death, and then his resurrection on Easter Sunday,

became our access to God.

Prayer: “Lord, I

see that you were not just angry but also hurt that they had turned the sacred,

simple, holy place into a market – the way we in our society make everything

into a market, all about money and getting. You judged all that and tried to

clean it up – along with our vapid religiosity that vainly imagines a few quick

prayers will get you to do our bidding and then you will leave us be. I am as

weary as you were with a thin, self-indulgent faith. Clean up my soul, and your

church.”

Holy Tuesday

Jesus was relentless,

fearless, clearly on a mission from God, ready to lose anything to attain

everything. After the drama of Palm

Sunday and the ruckus of Jesus' Monday morning rampage through the temple,

Jesus probably should have stayed home in Bethany, or fled during the night to

safety in the north where he'd come from.

But instead, Jesus walked

right back into the temple to face shocked, mortified, angry clergy and laity,

and began talking - at length. He didn’t win any friends by foretelling a

day when not one stone of the temple would be left upon another. The crowd had to laugh: Herod’s masons had built a seemingly

indestructible temple, with flawlessly cut, massive blocks, the largest

measuring 44 feet long, 10 feet high, 16 feet wide, weighing 570 tons. His

words seemed ridiculous – but still caused offense.

He was only getting

started that Tuesday. Matthew shares 212

verses of Jesus talking (chapters 22-25), including some of his most famous

teachings. And don't his words carry a much heavier freight since we know

he was in the final couple of days before his death? That Tuesday, he

exposed the faked religiosity of the pious Pharisees, he wept over the Holy

City which had lost its way, he warned the disciples of the perils of living

into the Truth. Jesus clarified that our salvation depends on whether we

feed the hungry and welcome the unwanted. Devious men tried to trick

Jesus with a question about a woman with several husbands: to whom would she be

married in heaven? For Jesus, the glory of hope is too large, too

wonderful to be shrunk to earthly proportions, or limited by the way we do

business down here.

We can picture him moving

about within the temple precincts, stopping under a portico, then strolling

down the large stone staircase, standing for a while near the gate, probing,

questioning, listening and yet ruminating at length. Take some time on

this Holy Tuesday to read Jesus' words from his Holy Tuesday: Matthew

21:23-25:40.

Prayer: “Lord, we are so grateful that on your final Tuesday

you had so much to say. We need to hear

and heed your thinking – although your Tuesday words are hard. We might prefer easy platitudes or simplistic

spiritual niceties – but in truth we are eager to hear and embrace your deeper,

riskier, more satisfying truth. I will

make time to read your words, and to ponder them, even when they expose the

triviality of my faith, and my lackluster half-attempts at following you.”

Holy Wednesday

Wednesday of Jesus’ last week. Frankly, we have no idea what happened that

day, besides the usual sunrise, meals, maybe chores, rest, casual

conversation. It’s often that way, isn’t

it? – the day before the most important day in your life, the dark day that

proved to be an unexpected plot twist in your journey, you weren’t doing

anything in particular.

Somehow I like the idea that, during a week of

intense activity for Jesus, we have a blank day, on which nothing earth-shaking

took place. Did Jesus simply chill with

his friends in Bethany? Did he teach someplace, or heal someone, but

nobody wrote it down? Did he visit two or three people privately?

Surely a public person like Jesus had private relationships, perhaps with

someone like Nicodemus or Joseph of Arimathea - or maybe he took a long walk

with Peter, Mary or John. Could it be he simply withdrew from people and

activity and prayed? Quite often the Gospels tell us "Jesus withdrew

to a lonely place to pray" (Luke 5:16, Matthew 14:23); if this was his

habit, his sustenance, his greatest delight, wouldn't he have done so during

Holy Week?

I also like the idea that Jesus is bigger

than what we know. John's Gospel ends by saying "There are many other

things which Jesus did." We hope so, and we even experience this

ourselves, for the fruit of Holy week is a crucified and risen Savior, who is

active today, not only continuing his ancient work, but doing new things.

Prayer: “Lord, sometimes I associate you only

with the weighty days. I forget you know

the normal, seemingly dull days too. I

assume that on Wednesday you were on intimate terms with God. I pray that

this could become my own habit of mind and heart. Be near me, Lord Jesus, at work, driving,

cleaning, reading, conversing, eating, waking and sleeping, even on a

Wednesday, mid-week.”

Maundy Thursday

“Maundy” is derived from the same

ancient root as our word "mandate." Jesus issued a mandate: "Do this in

remembrance of me." Today, we do.

So many of Jesus' meals were memorable! Pious people complained that he "ate with

sinners" (Luke 15:2). As a dinner

guest, he let a questionable woman wash his feet (Luke 7:36), and another

anoint him with oil (Mark 14:1). He suggested that when you have a dinner

party, don't invite those who can invite you back, but urge the poor, blind,

maimed and lame to eat with you (Luke 14:14).

His most memorable meal though was his last. For the Jews, it was Passover, the most

sacred of days when they celebrated God’s powerful deliverance of Israel from

Egypt; the menu of lamb, unleavened bread, and drinking wine symbolized their

dramatic salvation.

Jesus must have struck the disciples as oddly somber on such a festive

night. He washed their feet, then spoke

gloomily about his imminent suffering. As

he broke a piece of bread, he saw in it a palpable symbol of what would happen

to his own body soon; staring into the cup of red wine, he caught a glimpse of

his own blood being shed. We still use

the words Jesus spoke on that Thursday when we celebrate the Lord's Supper now.

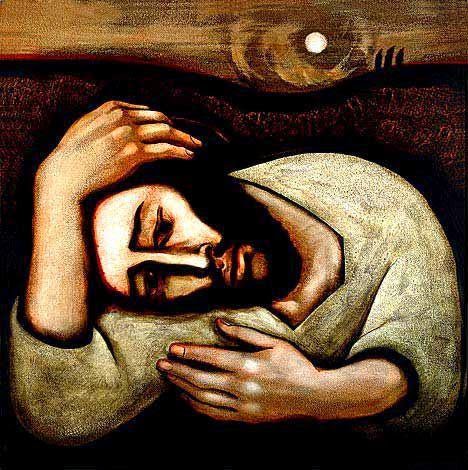

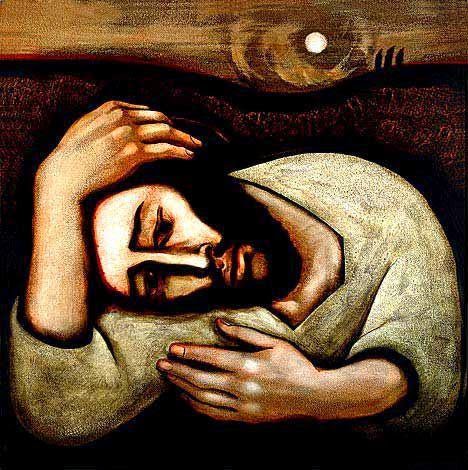

After an awkward, poignant conversation with his friends, Jesus walked

out of the walled city of Jerusalem to the Mount of Olives to pray in the

garden called Gethsemane. Kneeling in

anguish, Jesus prayed "Not my will, but Your will be done." But no slight hint of fatalism was in his

heart; Jesus’ mood wasn’t resignation: he

actively and courageously sought and embraced God's will, which isn't some dark

luck, but is when we with trusting faith go where God leads us, no matter the

cost.

After an awkward, poignant conversation with his friends, Jesus walked

out of the walled city of Jerusalem to the Mount of Olives to pray in the

garden called Gethsemane. Kneeling in

anguish, Jesus prayed "Not my will, but Your will be done." But no slight hint of fatalism was in his

heart; Jesus’ mood wasn’t resignation: he

actively and courageously sought and embraced God's will, which isn't some dark

luck, but is when we with trusting faith go where God leads us, no matter the

cost.

Jesus mercifully bore Judas’s betrayal, then was arrested. During the night, charges were trumped up,

witnesses were compelled to lie. The

proceedings were highly irregular... Who

was responsible for Jesus' death? The

Jews? The Romans? You and me? The Jews handed him over to the Romans, the

Romans handed him back to the Jews, the disciples handed him over. No one wanted to be responsible, and so they

(and we!) are all guilty.

Ultimately, God was responsible for this riveting, revolutionary

enactment of divine love and holy determination to be one with us, and to save

us. Through that dark Thursday night in

detention, Jesus was abused, mistreated, his destiny sealed. Holy Thursday waited all night for the chilly dawn

of the day with the paradoxical name: Good Friday.

Good Friday

What time is it? All day, this Good Friday, keep an eye on the

clock. Earlier this morning, at 6am, Jesus faced a mock trial, was treated

cruelly, yet took it all peacefully. By 9am,

Jesus’ wrists and ankles were gashed and shattered by iron nails, the cross

slammed into the ground; the snide snickering of onlookers began. At noon the sky grew eerily dark; then at 3pm

Jesus breathed his last.

We ponder that old hymn, “What

wondrous love is this?” Julian of Norwich offered this moving thought: “The

love which made him suffer surpasses all his sufferings, as much as heaven is

above the earth.” Today we read and

reflect on the profound words of the prophet

Isaiah: He was despised and rejected,

a man of sorrows, acquainted with grief. Surely he has borne our grief, and

carried our sorrows. He was wounded for our transgressions, bruised for our

iniquities, with his stripes we are healed. He was afflicted, yet he opened not

his mouth, like a lamb led to the slaughter; they made his grave with the

wicked, although he had done no violence (Isaiah 53).

Without the holy, divine love, without God’s

eternal plan to use this day to bridge the chasm between heaven and earth,

without God’s merciful determination to share in our sufferings and redeem us,

this Friday would be relegated to the history books, perhaps with a sad title

like Dark Friday, or Tragic Friday. But

we dare to call it “Good Friday.”

In the throes of death,

Jesus cried out, "My God, why have you forsaken me?"

Doesn't this leave us space to cry out in the darkness when we seem

forsaken by God? God did not remain safely aloof in heaven, but God

entered into human suffering at its darkest. Just as Jesus stretched out

his arms on the cross, so God envelops us in a love that even death could not

defeat.

In the throes of death,

Jesus cried out, "My God, why have you forsaken me?"

Doesn't this leave us space to cry out in the darkness when we seem

forsaken by God? God did not remain safely aloof in heaven, but God

entered into human suffering at its darkest. Just as Jesus stretched out

his arms on the cross, so God envelops us in a love that even death could not

defeat.

Be still, and quiet, as much as you can this day. Ponder the suffering, and love embodied in

the Cross.

Holy Saturday

We can

ponder Hans Holbein’s painting of Jesus lying in the tomb. But can we fathom the sorrow, the guilt,

doubts, disappointment and fear those who knew and loved Jesus felt between his

burial on Friday and his resurrection on Easter Sunday?

God could have raised him

immediately. But God waited. And we wait.

We have all found ourselves in the throes of some numb day, our own Holy

Saturday. We’ve endured Good Friday, the

losses – but there’s no new life yet.

“Those who wait on the Lord shall

renew their strength” (Isaiah 40:31). “I wait for the Lord, more than watchmen

for the morning” (Psalm 130:5). Saturday was, for them, the Sabbath, a day of

rest. Jesus rested in the tomb; God

rested in heaven. And so, with the disciples,

and Jesus’ mother, we wait wait this day, and every day, trusting the God we

cannot see, resting in the hope that Easter really is coming.

Easter Sunday

On the third day, Sunday, women came to the

tomb, but Jesus was not there, and then he appeared to people over the next few

weeks. Easter, constantly doubted, forever yearned for, the vortex of our

faith.

Easter, as happily

familiar as flowers in Spring or birthday parties growing up – and that very

familiarity tricks us into missing the

utterly unexpected shock of resurrection. Dead people stayed dead – until Jesus was

raised. Nothing automatic here, no silly

sentiments about the memory of someone living on. Nature itself was happily subverted; the

dreaded enemy, death itself, toppled.

But

Easter isn’t primarily about us. God raised

Jesus – and ours is to praise you and extol the wonder of Jesus. How great thou art. God is incomparably wonderful, powerful, and

tender. Yes, benefits come to us because

of Jesus’ resurrection – elusive glories like forgiveness and hope. But on Easter, we want to stop, and simply be

awestruck at the grandeur of grace that is the heart of God – and like the

first witnesses to Easter, we ask the risen Lord what tasks we might fulfill in

the wake of it all.

.jpg)