It occurs to me that problems creep into all our relationships when we make a few fundamental errors, like (1) I assume I know how you feel, or (2) I presume to know what your life is like without being there myself, or (3) If there is a problem, it must be your fault, or (4) My life, my perspective, my feelings are normal, and yours are the outliers, or (5) I tell you that you should feel differently, or worst of all (6) I simply won't listen. A recipe for disaster in a marriage, among friends or family - and in our country when it comes to race.

The Bible's persistent project is about getting inside the skin of other people. God did this in Jesus: instead of treating us as distant failures, God lived our life from the inside out. Jesus talks (no, he listens!!) to a Samaritan woman, tax collectors, a thief on the cross, Romans, and all the people nobody else listened to.

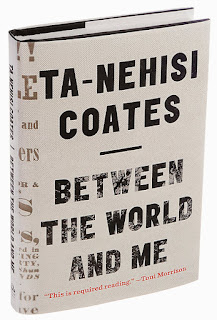

The hardest, most painful book I've read all summer is Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates. With searing candor and rising intensity, he shares what it feels like to be black in America. He will make you shudder, tremble, and blush - and then a light bulb pops on every other page or so.

Coates explores why young street blacks can be loud and rude, why blacks fear the police, what it's like to be viewed with suspicion no matter what you do, how "nobody can be Jackie Robinson every day," how parents tell their children they must be on their guard and be 'twice as good' or they will discredit all blacks - but white parents don't tell this to their children. A friend of his was killed by a plainclothes police officer in a cruel, ridiculous case - and Coates says "he was killed not by a single officer so much as he was murdered by his country and all its fears."

With every fiber of our being, we white people leap to defend ourselves, to explain why Coates is really wrong, to declare "I'm not racist." But in the Scriptures, listening, not defensive chatter, is the beginning of wisdom. Jesus' brother said "Be quick to listen, slow to speak" (James 1:19). "The way of a fool is right in his own eyes, but a wise man listens to advice" (Proverbs 12:15). Paul urges us to "Weep with those who weep" (Romans 12:15). Building relationships and community requires nothing less.

It's also interesting that Coates doesn't ask the white community to do anything at all. He's not blaming so much as simply telling what it's like, narrating his tory - and it's hard to deny anybody the right to tell how they experience the world. When he speaks of "fear" it's white fear, it's black fear, it's everybody's fear. He does redefine the American "dream," in a way that is haunting and closer to some deep reality than we'd care to admit.

People want to rush out and do something this week about race. But how do you build trust in a week? I enjoy several friendships with African-American clergy; we trust and love each other. One thing I know for sure: it takes time. I've been at it for 30 years. And something else: it is mine to do more listening than talking, and it is not mine to offer fixes. White people have always taken charge, haven't they? Ours is to listen, try to understand, feel pain, let somebody else lead on this, and then move forward courageously and hopefully together.

So start now to build relationships that will matter later on, and we'll need them later on. And of course, pray - which can be less of "Lord, hear our prayer," and more "Speak, Lord, your servants are listening."

.jpg)